And arguably, in my particular case, by the rigidity of the Royal Navy and obtuseness of one medical officer.

There were special circumstances. Perhaps, when one looks at individual cases, circumstances are always special.

There were special circumstances. Perhaps, when one looks at individual cases, circumstances are always special.Growing up, I was only dimly aware my grandfather had ever existed. Now, through that curious way things have of trickling down through families, I have hundreds of photos he took, dating back to 1912.

No doubt it is from him, via my father, that I inherited my fascination with photography.

As a child I knew the photos, not by him but of him, that hung on my grandmother’s walls.

The one of him probably about 30, already a little gaunt, in naval uniform. The other elderly, grey-haired, in the vegetable garden behind their little terraced house in London.

Elderly? He was two years younger when he died than I am now.

But that was already a lot older than most of the men who were sent to war.

Clive Semmens was 50, and newly toothless, when he was called up in 1939.

This I have learned only now, through acquiring a handful of old pocket diaries – his and my grandmother’s.

Mostly they record only such mundane things as meetings, lists of letters sent and received, rent paid, vegetables planted.

Mostly they record only such mundane things as meetings, lists of letters sent and received, rent paid, vegetables planted.In his case there are also times of sailings – “Weighed anchor Gibraltar 10.30” or “Anchored Shanghai 5.10a.m.”

One day in 1926 he notes: “Tried to get to Stamboul.”

The following day he records: “Got to Stamboul.” There is no note of what he made of the place (now known as Istanbul), though I have a dozen photos he took there (including the one below) – as I have of Gibraltar, Shanghai and many other exotic places.

It was in 1905, as a 16-year-old, that he followed his two elder brothers into the Navy.

Though he never conquered his sea-sickness, and always refused his rum ration, he remained in service up to 1929 in the engine-room of successive vessels.

Though he never conquered his sea-sickness, and always refused his rum ration, he remained in service up to 1929 in the engine-room of successive vessels.But it is my grandmother’s diaries for 1939 and 1940 that have shed a new and poignant ray of light.

“Saturday, August 19, 1939: Clive’s holidays started.

“Tuesday 22: Went by car to Rustington. Picked some sloes and blackberries on the way. Lovely weather.

“Wednesday 23: Clive received a telegram recalling him to barracks owing to international situation. Has to rejoin by noon tomorrow. Clive had the last tooth out.

"Thursday 24: Clive left home 8am to join the barracks. With his mouth still bleeding and not a tooth in his mouth he is passed as dentally fit and sent to a destroyer the same night!”

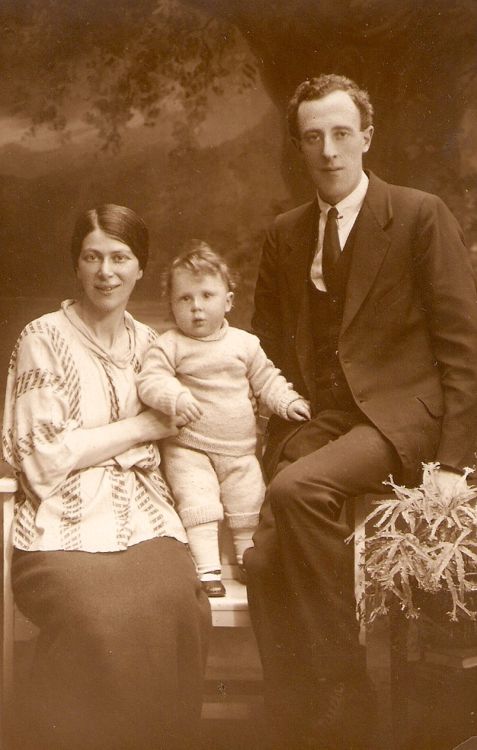

It was ten years since he had completed 24 years in the Navy, including active service throughout the First World War (pic below). Now, after a decade in civvy street as a radio engineer, he was back below decks as a “naval pensioner under 55”.

For the first few months of war he was on almost constant patrol in the Channel, escorting troop ships and clearing mines.

By an odd chance, he was home on his first leave at the time of the Dunkirk evacuation. The diary for these days includes more mundane detail than at almost any other time.

“Thursday, May 16, 1940: Clive’s leave started at noon; left Chatham 1.30pm, arrived home, after shopping in Greenford, about 4.30.

“Friday 17: Clive planted two rows haricot beans, one blackcurrant, 12 celery plants. Went to do shopping in the car.

“Sunday 19: Windy, warm, sunshine all day. Planted out one marrow, four cucumbers. Clive worked all day in the garden.

“Tuesday 21: Bright, sunny but windy. Went for a ride to Burnham beeches in the afternoon, had picnic tea there.

“Monday 27: Helped Clive to earth up the air raid shelter.

“Tuesday 28: Spent a few hours in the garden with Clive. Last day of his leave. Position very serious.

“Wednesday 29: Clive went back to his ship. I went to the station with him. Fine at first, clouds gathering in the afternoon. Late in the afternoon thunderstorm. Washed, dried and ironed.

“Friday June 7: Letter from Clive. Posted one to him.

“Sunday 9: Heaviest thunderstorm of the season. First of own strawberries for dinner. After the rain air raid shelter has several inches of water.

“Monday 10: Baled water out of the air raid shelter, hoed the onions.”

Added later in different ink: “Clive’s ship bombed off Le Havre, two bombs explode in the Engine Room. Clive injured.

“Tuesday 11: 8.30p.m. Telegram informing of Clive having been injured on war service.

“Wednesday 12: 4.15p.m received telegram informing of his having been admitted to Haslar Royal Naval Hospital, Gosport, seriously ill with injuries. Left at once for Gosport, arrived there about 9pm and told he is dead.

“Saturday 15: Clive buried at Gosport Naval Hospital at 11am with Naval Honours. Dorothy and Jim came, by car. Sis and Percy arrived just in time for the funeral. From a talk with the lieutenant of his ship I found Clive was conscious after the explosion.

“Wednesday, August 7: Received from Haslar Hospital Clive’s last-minute things – dentures, matches, cigarettes, handkerchief, magnet and spanner.”

No comments:

Post a Comment